A story of Jeeps that worked hard — and played hard — in small-town America

by Dan Montgomery

The primer-gray Jeep in front of me had been through a lot: A decade of granny-gear hay baling; weekends bouncing along rocky trails; school nights dragging Main Street; and a lot of just everyday driving to work and back home.

Like most of the other Jeeps I grew up around, it had probably been high-centered on rocks, axle-deep in mud, skid-plate deep in snow and floorboard-deep in water; driven too fast on twisty dirt roads in the mountains and flat out on straight dirt roads in the desert; lifted by a farm jack, pulled by a winch and towed by a pickup. It had, for sure, been caked with mud and scrubbed clean with elbow grease. This Jeep was a character in a lot of stories, including a couple of mine.

Paint under a front fender reveals and the factory red paint and the 1970s yellow paint on Robert Miller’s CJ5, the last known survivor of his grandfather’s fleet of work Jeeps.

Walt Sphar says it started with a guy named Hot Rod.

Ed “Hot Rod” Timmons stopped in Likely, a small — no, tiny — Northeastern California cattle town, one summer day in the mid-1950s to show the local ranchers why they should buy a Willys Jeep instead of a tractor.

Sphar, who has run a trucking company out of Likely for decades, remembers Timmons zipping a Jeep around in tight circles. Timmons also, no doubt, engaged the front hubs, dropped his Jeep into low-range, four-wheel drive and gassed it to show just how low it could gear down. He probably let his Jeep claw a front wheel up the side of a cinder block or railroad tie. He would have touted the removable top and doors. He likely kept returning to the magic made possible by the transfer case: Power to all four wheels.

The ranchers kept their tractors, but Timmons’ demonstration must have made an impression on Robert Miller, who ran a haying outfit based in Susanville, 90 miles of high desert and mountains south of Likely.

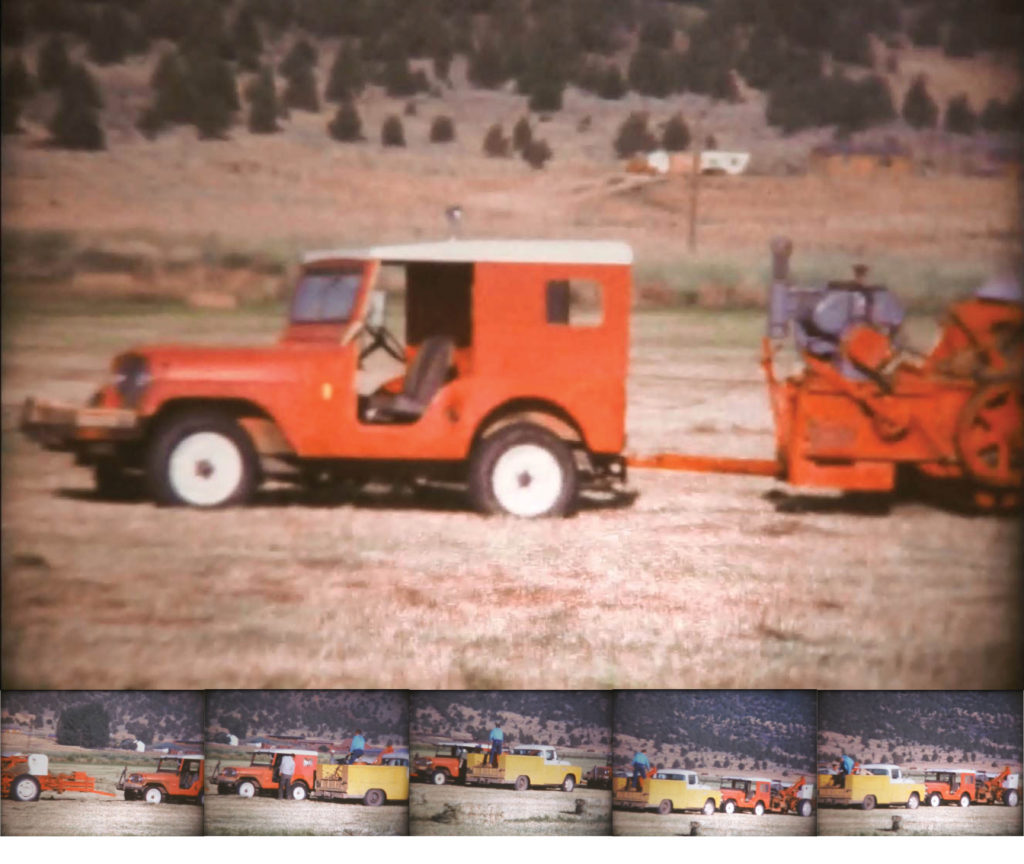

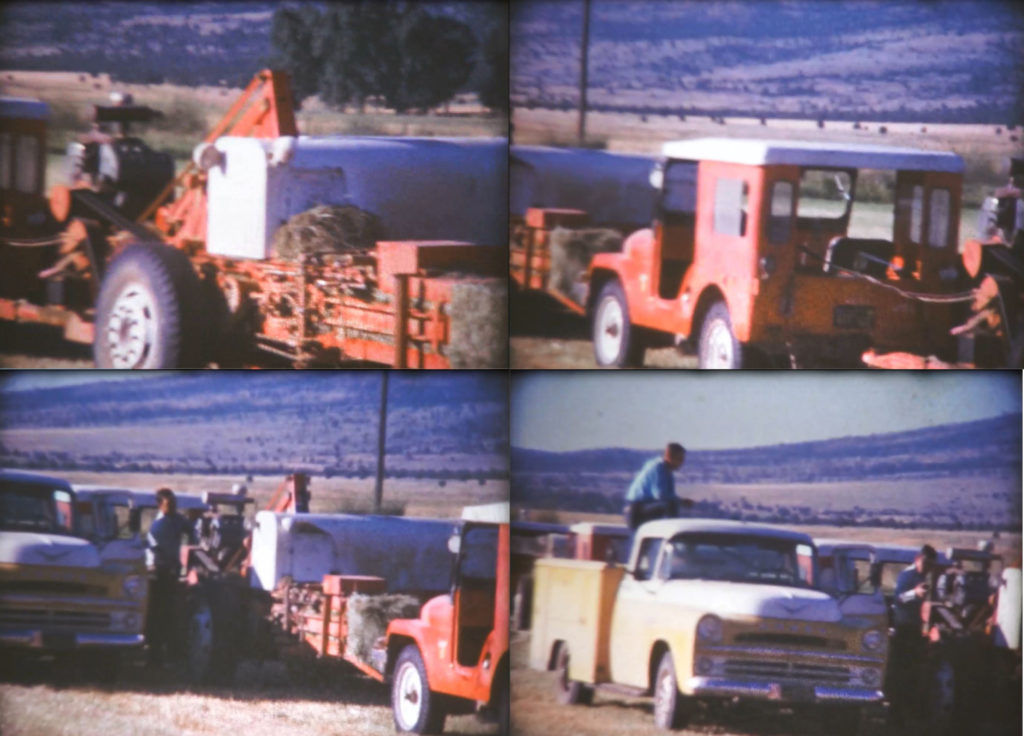

Before long, Miller’s Custom Work owned a 1956 Willys CJ5. Miller added two more in 1959. Then two 1962 models. They were custom ordered, with matching red-and-white paint jobs (but some had black windshield frames), metal tops and the optional limited-slip rear differential. They all had screens over the grills to keep chaff and straw out of the radiators and two rear-facing spotlights to illuminate, when necessary, one of Miller’s matching red-and-white New Holland hay balers. No more tractors.

These Jeeps started out as the Willys company intended them; as field tools, a mechanical investment meant to help Miller and his cattlemen customers cut, bale, load, and transport more timothy grass and alfalfa in less time. But Robert Miller’s Jeeps became something more. Their influence was small, but still significant and long lasting, spreading from Likely’s Flournoy and Christensen ranches to the thousands of miles of dirt roads and trails that criss-cross Northeastern California, to Susanville’s Main Street, to the country roads where teenagers drag race under cover of darkness, and to my own my family’s driveway, campsites and daily commutes.

I spent part of my youth riding in Robert Miller’s Jeeps, admiring those same Jeeps reborn as dust-covered rock hoppers and rumbling street machines, and learning to drive in a Jeep worked on by some of the same hands that maintained, then modified, those red and white CJ5s.

Most of the Miller’s Custom Work crew from the late 1950s through the early ‘70s died years ago, but one employee, John White, is still around to talk a little about the golden era of Robert Miller’s four-wheel-drive-powered hay operations. White speaks with pride about the way his boss used the Jeep fleet to get the hay in faster than the competition.

“Bob Miller was a businessman, see. He had this figured out,” White says. “He said, ‘We’re a production outfit, not a screw-around outfit.’

“Bale that hay. That’s what we were after.”

That’s what cattlemen were after, too. Billy Flournoy, one of three brothers who now run the sprawling (like, 20,000-acres) Likely Land & Cattle Co., remembers that’s why the Flournoy forebears hired Miller’s Custom Work year after year: They moved hay, thousands of tons each summer, in a hurry.

For nearly two decades, Robert Miller’s CJ5s were part of his winning business formula.

“A Jeep would outpull a tractor in boggy ground,” White says. “They would pull a bigger load and not spin out, and those New Holland balers probably weighed more than a ton and a half.”

The Jeeps could be driven quickly from job to job, or unhitched for a sprint back to the barn or to run errands in town.

And: “Those Jeeps never broke down,” White says. “They didn’t heat up or anything. They were combat machines originally, dammit.”

The Jeeps could also carry a lot of wire, and that’s important. Hay balers spit out several feet of wire to bind every bale of hay, and Robert Miller didn’t like the inefficiency of having someone driving around delivering wire to his fleet of balers. The back of each Jeep easily held four 94-pound rolls, each inside a cardboard box with a distinctive circular opening that allowed wire to spool out. Miller’s Jeeps carried four more boxes on sturdy trays attached to their front bumpers. Miller’s men were all mechanics and welders. It was nothing for them to fabricate the heavy-steel, grate-bottomed trays, bolt the tow bars to the front of the trays, and relocate the license plate to the front of the passenger-side fender. Now each driver could carry his own supply of wire (or extra gasoline), and, with 400 extra pounds on the front axle, each Jeep got a lot more front-end traction to boot.

My father, Bob Montgomery, worked for Miller’s Custom Work. He ran Caterpillar bulldozers up pine and fir-forested mountains, building logging roads. He welded, repaired equipment and, each summer, returned to Likely’s lush hayfields. (Modoc County is mostly arid, sagebrush-and-juniper country, but many of the valleys are wet, green and fertile.) Dad cut hay with swathers, baled hay behind the wheel of a Jeep, and stacked bales of hay on flatbed trucks. (Some of that hay would have been trucked out by Walt Sphar 18-wheelers.)

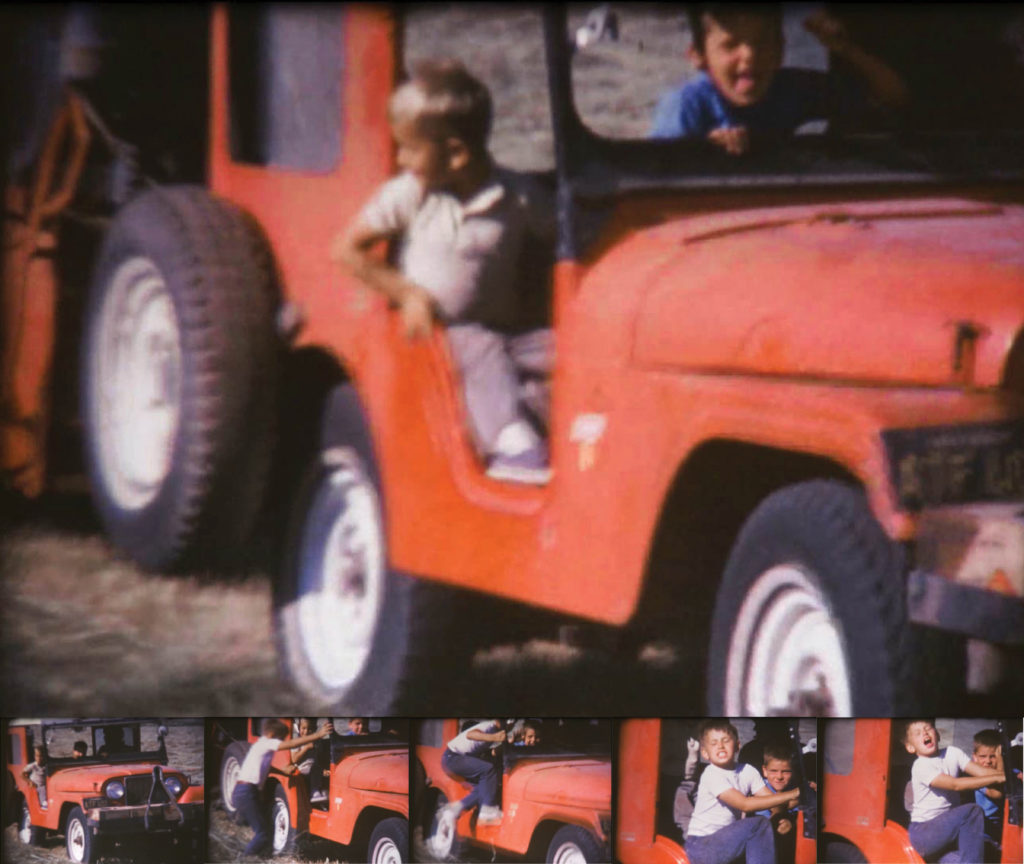

I was the middle of three brothers. Our mother shuttled us north to Likely for a couple of weeks most summers in the 1960s and early ‘70s. On the Christensen ranch, I learned to rope a fence post, tap my toes to Johnny Cash and jump in and out of a moving CJ5. Robert Miller’s yellow-and-white Dodge trucks did not interest 8-year-old me. Riding a swather was more like it, and the Jeeps were best of all. They were small, but strong. They looked neat. And there was usually an empty seat for a kid.

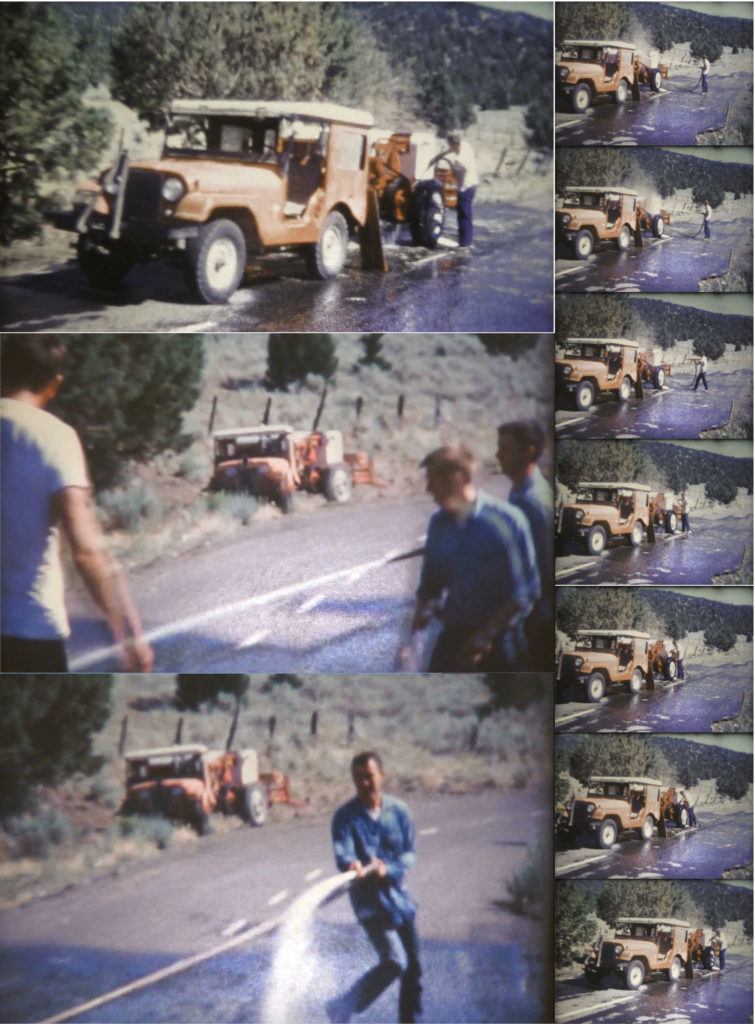

Sometimes, on weekends, Robert Miller’s CJ5s were hosed down, loaded with passengers and Olympia Beer and driven into the Warner Mountains, where the Jeeps pulled themselves over rocks and crawled up steep embankments. This is where I imagine my dad got the idea of getting a Jeep for himself. He wasn’t the only one, and when Miller’s Custom Work phased out of the hay-baling business (as tractors became more powerful and more comfortable, and as haying needed less manpower), the red-and-white Jeeps filtered out of the business and into private use.

Susanville was bound to be a Jeep-heavy town. Steep hills, dirt tracks, hunting, ranching, snowy winters and general middle-of-nowhereness guaranteed it. But Jeep culture got an extra push from Robert Miller and some of the men who worked for him, including John White and my dad. They joined up with other gearhead Jeepers in the Lassen Four-Wheelers club and proceeded to fix up Jeeps for both Main Street cool and Rice Canyon performance. Other Jeeps around town also found V6s and V8s where their four-cylinder Go-Devils and Hurricanes used to be. Most of Susanville’s teen-age boys still favored Detroit muscle, but a significant minority wanted to drag Main Street (the dominant local teenage recreation) in a hopped-up Jeep. I could recognize individual Jeeps (and the rare Land Cruiser) at a distance: Doug Forrester’s orange flat-fender, Jim Donahue’s pale yellow CJ5, Frank Ernaga’s blue CJ3B.

John White bought a Jeep from his boss and turned it into a showpiece, with bright rims, roll bar, canvas top, off-road tires and a Chevrolet V8. The boss was impressed. One day, he asked White if he could take the modified CJ5 out for a test drive.

“He was gone three hours!” White says. “He came back and said, ‘What would it take to make mine like that?’ ”

It took a week and a half for White and another mechanic to install all the goodies in Miller’s ‘62, including power brakes and a Chevy 350 V8.

“These were all stock engines, though,” White says. “No hot rods — they get hot, it’s no good. You want to idle down, you don’t want to rev up, see? But you got lots of power.”

White and Miller didn’t know it, but their former farm Jeeps were about to become local legends — as hot rods. I first heard it whispered about when I was 13 or 14: John White’s and Robert Miller’s Jeeps could do wheelies, but don’t say anything, because John White and Robert Miller don’t know about it. John’s son, Johnny, and Robert’s grandson, Bobby: They were the ones popping wheelies.

“I’d be gone off somewhere working, and Johnny and Bobby, they’d take the Jeeps out and they’d drag,” John White recalls. “Bobby blew Bob Miller’s Jeep all to hell — just tore everything inside the differential to bits. What’d they’d do is let some air out of the tires until they were about half flat, to get some traction, then they’d pull wheelies!”

More on those wheelies later. I do know that “Bobby,” now Robert Miller, must have been forgiven. He soon took ownership his grandfather’s other ‘62, which he tricked out with a V8 engine, roll bar, off-road tires, stereo and a bright yellow paint job.

My parents had bought their Jeep a few years earlier, in 1969. On the way to check out an old Jeep my dad’s uncle owned, we stumbled across a straight and rust-free ‘46 CJ2A. Mom and Dad snatched it up for, if I remember correctly, $400. With help from the Lassen Four-Wheelers wrench gurus, our Jeep gradually took on fresh blue paint, shiny chromes, a black Bestop, checkerboard-pattern tires, side pipes, power steering, a Borg-Warner four-speed transmission, a Warn overdrive and an “odd-fire” Jeep V6 (a Buick design, but with a heavy flywheel). Dad thought V8s were asking for trouble. Like wheelies, maybe.

For a few years, as long as all of us boys could still squeeze inside, Dad’s Jeep was the family toy, our main source of recreation and an implement of nuclear family bonding. We traversed the local mountains and high-desert plateaus, usually with us boys standing up in the back, hands on the roll bar. We all learned to drive in the Jeep, taking turns behind the wheel on all but the roughest terrain. Our mutt, Pete, rode on the hood like a Mack Truck bulldog.

Eventually, the Jeep became my big brother’s ride. He and it survived several adventures, some of which my parents found out about (like the broken axle shaft), and some they didn’t (like putting the Jeep on its side). When Steve left for college, Dad got his daily driver back. But he eventually tossed the keys to my younger brother, Jeff. Middle siblings have a way of getting passed over in this sort of family turn-taking, but I got a few epic rides in, too, like the time I drove, fast, through a pond-sized, bumper-deep puddle at Eagle Lake, drenching Jeep, me and my girlfriend with mud. Or the time I broke the tie rod but limped home, backwards, after lashing the severed pieces to a fishing rod. Or the time … you get the idea. And as I write this, Dad’s Jeep is my Jeep, and, a half-century after he bought it, CJ2A Serial No. 77691 enjoys light-duty grocery runs and weekend drives around my home in Virginia.

When I started asking around about Robert Miller’s Jeeps, I had one main question: Were any still in Susanville? Not John White’s. He sold his after 30 years, when the body rust got too bad. Then he bought and fixed up another CJ5.

White thought Greg Valceschini, a local doctor, had one of the old Miller Jeeps. Nope, Greg’s father bought their ‘65 CJ5 new, but he did take it to Miller’s to have one of those front-bumper trays installed. Not for hauling baling wire during hay season. For hauling bucks during deer season.

Robert Miller, the grandson, is still in Susanville, and still Jeeping. He has a Rubicon now, but I thought he might know what happened to his namesake’s Jeeps. He’d certainly know the full wheelies story.

After our re-introductions (I would have been a bone-skinny teenager when he last saw me) Robert chuckled and filled me in on the Great Wheelie Adventures. After partially deflating the rear tires, he’d put a couple of guys in the back seat, behind the rear axle, get going in reverse, coast, shift, rev, and pop the clutch.

It was all good fun until the time the front end snapped skyward, a crashing sound came from the rear, the engine raced, the front end slammed back down to earth, and the Jeep sat there, perfectly stationary. Another good thing about transfer cases: Teenagers can destroy the rear differential and still drive home to confess their sins to parents and grandparents.

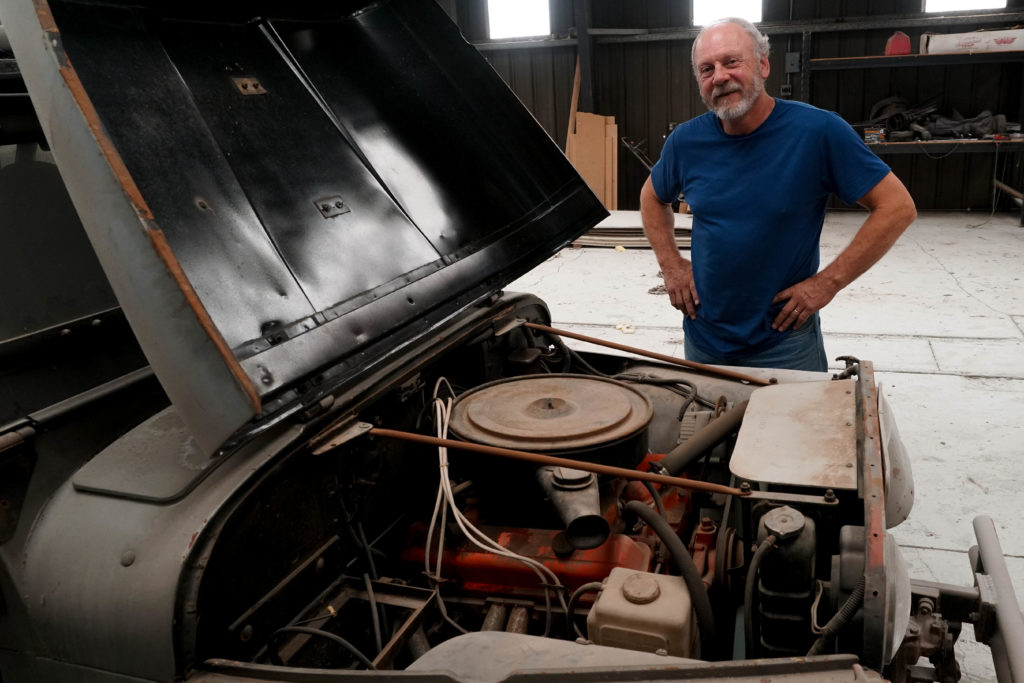

Robert led me to a shop outside of Susanville. We walked past the Caterpillar 46A bulldozer my dad piloted all those decades ago. Robert opened the door to the shop and there, parked and resting, was the last, as far as anyone I could find knows, of the Miller’s Custom Work Jeeps. It looked different, thanks to a fiberglass top and a coat of gray primer.

But under the hood sat the same 307 Chevy Robert installed when he was a teenager, mated to a four-speed transmission he got out of a Dodge truck. I knelt to get a better look inside a front wheel well. It looked like a Jackson Pollock painting made with yellow paint sprayed on in the 1970s and red paint sprayed on in Toledo, Ohio, in 1962.

I stood up and stepped back for another look. The windshield frame was black, a screen covered the grill, and the license plate, California ATF 402, was mounted on the front of the passenger side front fender.

I have a stack of Kodak-yellow boxes on my desk: Home movies from the 1960s. One reel shows, in 16 flickering frames per second, 8-year-old me sticking my face through the flipped-up windshield of a baler-towing red Jeep (driven by my mother, incidentally) bearing California license plate ATF 402.

And here, 51 years later, was that Jeep, parked in the middle of Robert Miller’s shop. Retired. Though maybe not retired for good.

“Not long ago,” Robert had told me, “My wife asked me if I could fix it up for her to drive.”

About the author – Dan Montgomery has fond memories of his summers riding in Jeeps in the hayfields, despite the mosquitos. After 25 years as a newspaper reporter and editor and a stint as a middle-school English teacher, he now works for a social services agency in Virginia. He still has the family Jeep, which was once bomb proof, but nowadays breaks down regularly.

The original version of this story appears in The Dispatcher Spring 2020 magazine,

A photo gallery of stills from 8mm home movies (movie stills courtesy of Janice Montgomery) and photos of Robert Miller’s CJ5 (courtesy of the author) is presented here. Click on any photo to see the full version.

To see some of the 8mm home movies, click below.